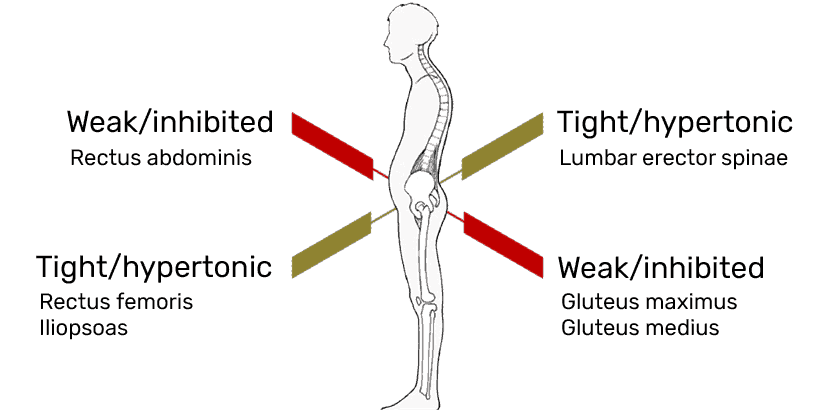

The lower cross syndrome is the result of muscle strength imbalances in the lower segment. Imbalances can occur when muscles are constantly shortened or lengthened in relation to each other.It is a common postural condition that affects the pelvis, hip joints, and lower back muscles.

It is a postural imbalance caused by muscular dysfunction in the lumbopelvic region. It is characterized by:

- Tight (overactive) hip flexors and lumbar extensors

- Weak (inhibited) abdominal muscles and gluteal muscle

The condition can affect a person’s posture and movement, as well as causing pain or discomfort. Treatment can involve strength training and stretching.

In LCS there is overactivity or tightness of hip flexors and lumbar extensors. Along with this there is under activity and weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side and of the gluteus maximus and medius on the dorsal side. The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well. This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the pelvis, increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine.

This imbalance creates a “crossed” pattern of overactivity and underactivity — hence the name “Lower Cross.”

Prevalence & Causes

- Common in desk-bound individuals, athletes with poor technique, and people with sedentary lifestyles.

- Often linked to prolonged sitting, poor core strength, and lack of mobility exercises

Epidemiology & Risk Factors

- Prevalence: Up to 75 % of office workers and 68 % of recreational runners demonstrate measurable anterior pelvic tilt in observational studies.

- Age: Peaks 20‑45 y when sitting hours and training loads are highest.

- Occupations/Sports: Programmers, drivers, cyclists, power‑lifters (deep lumbar extension under load).

- Contributing factors: Lumbar hypermobility, congenital hip anteversion, pregnancy / postpartum (hormonal ligament laxity + abdominal wall stretch), poorly periodized strength programs emphasizing heavy squats/deadlifts without complementary core‑glute work.

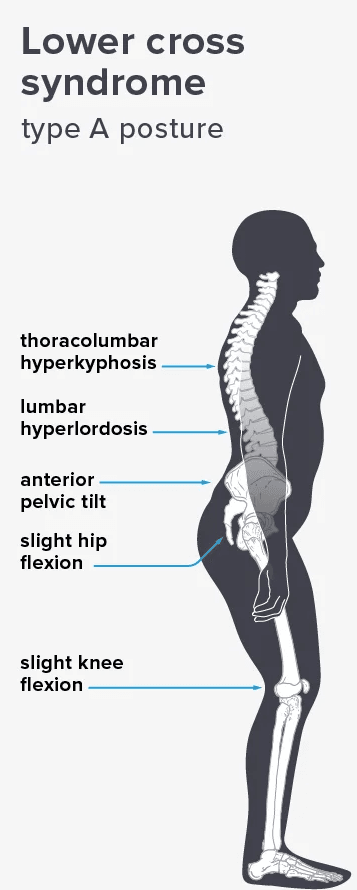

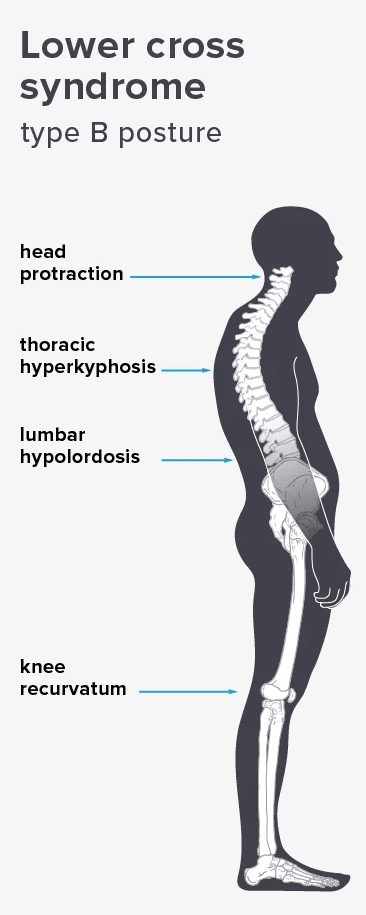

This muscle imbalance creates joint dysfunction (ligamentous strain and increased pressure particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, the Sacroiliac joint and the hip joint), joint pain (lower back, hip and knee) and specific postural changes such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external rotation of hip and knee hyperextension. It also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: increased thoracic kyphosis and increased cervical lordosis.

There are two known subtypes, A and B, of lower crossed syndrome.

- Type A: The first subgroup is the posterior pelvic crossed syndrome.”domination of the axial extensor”

- Type B: It is also called ‘The Anterior Pelvic Crossed syndrome. In this type the abdominal muscles are too weak and too short.

Clinical Presentation

- Postural signs (static):

- Pelvic ASIS sits 2‑5 cm lower than PSIS (palpation).

- Rib flare, abdominal protrusion, hyper‑lordotic curve, slight knee hyperextension.

- Movement dysfunction (dynamic):

- Overhead squat test: early heel rise, trunk forward lean, lumbar hyper‑extension (“butt‑wink” reversal on ascent).

- Gait analysis: decreased stride length, excessive anterior pelvic tilt at toe‑off; lumbar‐driven extension instead of hip extension.

- Symptom clusters:

- Dull lumbosacral ache after prolonged sitting or standing.

- Hip impingement‑like pinching in deep flexion.

- Recurrent hamstring or groin strains, patellofemoral pain (due to altered femoral IR & tibial ER coupling).

Assessment Battery (detail)

| Test | Target | Positive Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Test / Modified Thomas | Iliopsoas, rectus femoris length | Thigh fails to drop to table; knee flex <80 ° | Short/overactive hip flexors. |

| Ely Test | Rectus femoris | Early hip flexion during prone knee flex | Tight rectus femoris. |

| Prone Hip Extension EMG Timing | Glute max vs. erector spinae | Erectors fire ≥50 ms before glute max | Aberrant recruitment sequence. |

| Prone Plank Endurance | Core endurance | Holds <45 s with lumbar sag | Weak/inhibited anterior core. |

| Single‐Leg Bridge | Glute max strength | Pelvis drops or rotates | Glute weakness & contralateral QL compensation. |

| Digital Inclinometer | Pelvic tilt angle | >15° anterior tilt | Confirms structural vs. functional tilt. |

EVIDENCE

| Study | Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Akuthota et al. 2022 RCT (n=64 office workers) | 8‑week corrective exercise vs. control | ↓ anterior pelvic tilt 4.2 °, ↓ pain (VAS 2.3 → 0.8); ↑ glute max EMG amplitude 28 %. |

| MacDonald & McGill 2023 systematic review | 19 EMG studies | Consistent delayed glute activation (60‑120 ms) in LCS; core re‑training normalized timing within 6 weeks. |

| Noll et al. 2024 workplace intervention | Sit‑stand desks + micro‑break apps | 35 % reduction in new‑onset LBP episodes over 12 mo. |

Management Road‑Map

Phase 1 – Release & Mobility (Weeks 0‑2)

- Soft‑tissue: 60–90 s foam roll/ball on: iliopsoas, TFL, rectus femoris, lumbar paraspinals.

- Static stretches (hold 30–45 s × 3): kneeling lunge, prone press‑up extensions.

- Joint mobilization: Grade III/IV PA mobilizations at L4‑S1 (therapist).

Phase 2 – Activation & Motor Control (Weeks 2‑6)

| Exercise | Sets × Reps | Tempo | Cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supine dead bug with diaphragmatic breathing | 3×10‑12 | 2‑0‑2 | Flatten low back; exhale on leg drop. |

| Side‑lying clam with miniband | 3×15 | 2‑0‑1 | Keep pelvis stacked. |

| Glute bridge with posterior pelvic tilt | 4×12 | 1‑1‑2 | “Crack a walnut” between glutes at top. |

| Bird‑dog | 3×10/side | 2‑0‑2 | Avoid lumbar extension, brace core. |

Phase 3 – Integration & Strength (Weeks 6‑12)

- Compound lifts re‑patterned: hip‑hinge drill → kettlebell RDL → trap‑bar deadlift (maintain neutral spine).

- Anti‑extension core: roll‑outs, pallof press, farmer’s carry.

- Single‑leg work: step‑ups, Bulgarian split squats (focus hip extension drive).

Phase 4 – Power & Return‑to‑Sport (Week 12 +)

- Dynamic glute dominance: kettlebell swings, jump squats, sprint mechanics.

- Agility & deceleration drills integrating proper core‑glute timing.

Program Frequency

Release & Mobility: daily; Activation: 4–5 sessions/wk initially; Strength/Power: 2–3 × wk on non‑consecutive days.

Ergonomic & Lifestyle Corrections

- Workstation: Desk height allowing elbows 90‑100 °, monitor top at eye level, lumbar‑support chair.

- Micro‑break strategy: 2 min movement every 25 min of sitting (Pomodoro timer).

- Sleep: Side‑lying with pillow between knees or supine with small bolster under knees to reduce lumbar lordosis.

- Footwear & gait: Transition away from high‑heeled shoes; consider gait‑retraining if overstriding.

MUST READ – Upper Cross Syndrome: A detailed Overview